Blogs

- Muslims Should Not Trust Australian Courts!

- Why ICE agents continue shooting & shooting!

- Appointment of Greg Moriarty as Ambassador to the USA will damage Australia’s national security.

- Trump will Not give up Power – A Scenario!

- Cognitive blind spots

- AUKUS and Kim Jong Un

- David Gonski and Chris Minns

- Video on secret origins of AUKUS

- Peter Jennings would thrive in an authoritarian country.

- David Leser, a Jewish author & journalist, wrote:

- My 31 year Russian Saga

- Actor Russell Crowe: Hermaan Goring in Nuremberg

- “Foreign Affairs” magazine nonsense on AUKUS

- How China Can Succeed in Taking Control of Taiwan Under Trump!

- Trump Psychology and Capability compared to Famous Dictators

- Video of Putin’s Psychology and Leadership Style

- Trump’s Security Adviser Stephen Miller & Himmler-Bormann

- Video (and Text) comparing Putin’s rise and consolidation of power to other historical dictators

- ASIO chief Mike Burgess would be happy working for Putin

- Australia’s Racist NSW Police

- Trump’s Odessa for Greenland deal!

- Confidential Letter to Trump on AUKUS

- Why Do People Serve a Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin?

- Putin and his Lieutenants compared to Mao, Napoleon, Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin and Ataturk

- Russian Censorship Comes to Australia via Jews!

- Anne Applebaum writes like Trump talks

- Putin’s Successor if he is killed soon!

- Brittany Higgins false rape earned her $2m

- Lies of Mike Burgess, the Director General of ASIO

- Beazley, Richardson, Dibb are old men pushing sexy, ignorant group thinks.

- Jewish women Yvonne Engelman and Nina Bassat are Russia-type PR pawns?

- Bad News for Ukraine

- Group Think psychology of AUKUS and Option 2

- Putin says he follows Israeli Gaza example

- Henry Ergas praises Nazi “Will”

- What did we learn from the Tucker Carlson interview of Putin?

- Russian-Ukraine lessons on China

- Me and Colin Rubenstein – an Australian “traitor”?

- Cardinal Pell and David McBride

- Air Chief Marshal Houston & Hitler

- Albrechtsen plagiarises Goebbels

- Anatoly Chubais

- Assange and Defence

- Blair & Gadhafi

- Blair & Napoleon

- Brooks and Tett on policy psychology

- Cardinal Pell’s God

- Donald Rumsfeld

- Field-Marshal Keitel

- George Bush, Stalin, Mao

- Gillard & Duncan Lewis

- Gillard & Obama

- Gillard & Putin

- Gillard: psychological profile

- Gillard’s personal decision UN vote!

- Goering’s Wisdom

- History of anti-terrorist laws in dictatorships

- Howard & Sinodinos

- James Packer’s lieutenants

- Lateral Thinking

- Lawyer X, Huawei, National Security, Scott Morrison, Chinese in Australia!

- Major-General Cantwell & Matiullah Khan

- Medvedev & Obama

- Medvedev & Putin: “power corrupts”

- Morrison, Binskin and Napoleon

- National Security Myth

- Obama, Jefferson, slaves, murder, Nobel Prizes

- Obama’s Nobel Prize speech

- Paul Lodge (Family Court, Australia)

- Peta Credlin and Abbott, like Hitler-Bormann

- Peter FitzSimmons, George Pell, bias and group think.

- Psychologies of Putin and USA

- Psychology of Secret Courts / Military Tribunals

- Psychology of Supporters of Bush & Saddam

- Putin in 2000

- Putin Personality Cult

- Putin, Gillard, Abbott, Medvedev

- Putin: New Faces and Flaws in the Weave

- Putin’s dangerous reading

- Russia, NATO, Missile Defence

- Tony Abbott

- US Missile Defence

- Wendi (Wendy) Deng

- Why I support WikiLeaks

- Movie Script: Russia to Cambodia

- Trump Psychology and Capability compared to Famous Dictators

Personal Links

My 31-year Russian Saga

I first arrived in Russia in November 1991 after visiting Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland in an attempt to see “communism” before it disappeared. I was Chief Economist of an Australian bank but very bored after ten years of financial market analysis and commentary. My previous international travel had been limited to the UK, Western Europe, Japan, the USA and New Zealand but I expected that my wide reading – I had a history degree as well as an economics degree – would help me understand the collapsing communist world. My high economics profile led Australian Embassy staff in Prague, Budapest and Warsaw to help in arranging meetings with officials involved in economic policy – including with the head of the Hungarian Central Bank and the Polish Minister for Privatization. What I saw and heard in these countries was not too far from my expectations.

However, Russia (I visited Moscow and St. Petersburg) was “weird”! My attempts to meet senior Russian economic officials were less successful and chaotic than in the other three countries and I ended up having considerable free time. I was staying at the Intourist Hotel not far from Red Square and in the lobby began talking to an American man aged about thirty. He was not staying at the hotel but was there looking for some English language conversation. After some adventures in Eastern European countries where he apparently crossed one border without a visa because officials just waved him through because he was an American, he has snuck into Russia without a visa by hiding in some part of a railway carriage. Once inside Russia – and with no Russian language skills – he had been totally at sea and unable to leave until he met some Russians who arranged a fake visa for him and used him to move foreign currency across the border. He procured vodka for us by bribing someone on the hotel kitchen and he spend a day showing me around Moscow.

The shops in the main Tverskaya Street we basically empty and the only illumination of a night was the orange streetlights. However, my new American friend did take me to the Izmailovsky street market on the outskirts of Moscow where there was a greater variety of goods.

I also met John Helmer, an Australian journalist who also had his own unusual experiences in Russia. When – totally enthralled by the weirdness of Russia – I returned a second time in mid-1992, I rented Helmer’s apartment for about a week. Amongst other things he took me to lunch with a prominent Russian economic journalist, Mikhail Leontyev, who lectured me on the coming “successful” economic reform agenda. He totally dismissed the doubts that Helmer and I expressed and later was so disillusioned with the reform that he became a strong Putin supporter and spokesman for Igor Sechin at Rosneft. I do not recall hearing any anti-American or anti-Nato comments in Russia during this period.

On this trip I also met with Prof. Richard Layard, a well-known British economist, who was advising the Russian government on reform. I was very critical of his pushing “shock-therapy” even though he had no personal knowledge or experience of Russia. He, and a Polish economist who had travelled to Russia with him, had decided that: “There was less than 50% chance of this working, but it was worth a try”. I wrote about this, “Russian Reformers and IMF Get it Wrong”, here: See here: https://russianeconomicreform.com/

In Sydney I had met a Russian-Jewish man named Jack and on my third trip to Russia we joined together and met many people that he had remained in contact with. Several were in business ventures, including in nascent money market trading, and in this way I also met people who let me stay with them on my future Moscow visits.

One of the people we met was a Chechen man who had aspirations of taking his family to Australia, and – as I understand it – had future business dealings with Rene Rivkin. He took us to a meeting with a man described as “head of Moscow railways” and the discussion was about transporting goods outside of official arrangements. On another occasion I was offered the opportunity to buy a half-completed building close to the center of Moscow – but I declined!

In Moscow I lived in a variety of apartments thanks to Jack’s friends and contacts — ranging from a communal apartment not far from the Bolshoi Theatre to a very large multi-room apartment on Tverskaya Street owned by an elderly-woman who lived there alone.

Jack, one of his Russian-Jewish friends in Moscow, and I did try to establish a business venture, but differing expectations – and some criminal pressure on the man in Moscow — saw it go nowhere.

On my first two visits to Moscow the streets had been dirty but the weather meant that there was no snow. On later visits I found that fallen snow on footpaths had not been swept away and had turned to ice which made walking very hazardous.

I had seen an English language business publication somewhere in Moscow and decided to visit the organization producing it – which turned out to be affiliated with one of the many “banks” which had sprung up. I use the term “banks” only because this is what they were officially designated as, but most were money laundering shops or intra-group financiers with only one office.

I became very friendly with the two women who produced this publication, one of whom was named Evgenia, which eventually ceased because of lack of funds. I also met the very charismatic husband of the other woman who was later to be found dead in a forest tied to a tree after being tortured over some business dispute.

On this mid-1992 trip I had my first of a number of meetings with a young economist named Andrei Kozlov in the Russian central bank. He was later to become deputy head of the central bank and was shot dead in 2006. Some years later I was to meet a woman who husband had been killed after being shot with an automatic weapon in the lobby of their apartment building.

One day on a Moscow street I asked a boy for some directions. His name was Kostya and he spoke very good English. He was 15 years old and I became good friends with his family which lived in a large apartment slightly south of the Moscow River. It turned out that his father had worked in a senior position in the Russian film industry and had a very extensive collection of historical footage.

On the evening of 3 October 1993 Kostya and I headed down the Old Arbat Street, picking our way past barricades put up by protestors. I went back to my apartment on Kutuzovsky Avenue and when next day I heard gun-fire, I caught a taxi to the apartment of Kostya’s parents and then spent most of the day watching CNN as Yeltsin’s forces assault the White House. I would have liked to go out and get closer to the action but was uncertain about how to do this and concerned that I might miss something important being shown on CNN. However, that evening I did go to an area across the river from the White House and stood with a crowd watching tracer bullets in the sky.

I was horrified when, drinking beer in a popular bar that evening, I heard many Western foreigners hail the attack. I thought that this stupidity by Yeltsin was part of a series of events that eventually would lead to a Russian dictatorship.

I would have loved to have found a well-paid full-time job in Russia and was approached about this. Two things mitigated against that. One was that I had a young daughter in Sydney and needed to spend less time away from her. The other reason was my lack of language skills which was a hindrance to my basic approach to issues. I was later to confirm that I am just poor at learning a foreign language with my ill-fated attempts to learn Mandarin. This may partially reflect my complete lack of musical talent but it probably also reflects my personality which takes an analytical and reading approach to learning rather than gregarious and inane conversations for the sake learning new words and sentence constructions. In both the Russia and China arenas I have come across people who have done well because of their language skills rather than intelligence or analytical ability.

Back in Sydney I found a job as a banking analyst with stock-broking firm called BBY. I soon realized that this focus on financial issues was what I had tried to escape when I left my chief economist job and was both surprised and grateful when I learnt that several people at BBY had a private interest in a small funds manager group (called Pacific Gemini / Tiger Securities) investing funds in the Russian Far East and asked me to work in Vladivostok. This seemed promising because I could also spend a lot of time in Australia with my daughter.

I first arrived in Vladivostok late one night and was impressed by the well-lit harbor which had steep hills on either side. Daylight, however, revealed that the hills were largely rocky and barren of trees. The investment fund totalled only $US13 – but there were promises of more — was run by a man called Andrew Fox, an ex-Eurobond trader, who because of some apparent historical family connection had decided on an adventure to make money in privatized Russian assets. He had apparently floundered until he met and married a slightly older Russian women who was an accountant and showed him the way. One thing that I eventually noticed was that in nearly all Russian companies the General-Director (or CEO) was a man but the “chief-accountant” was a woman.” This was a significant advantage for women in a time of financial turmoil and “privatization”

Keir Neilson’s Australia based Platinum Asset Management was a small in investor in this fund and he came to Vladivostok for a visit. He was reasonably impressed with a couple of small entities and suggested that Fox buy shares in them, but most were clearly to be avoided. One of my most vivid memories was visiting an entity that made refrigerators (I recall that it was called Rodina) with 15 or so of its executives sitting around a large table and the Director-General telling us that they would all become rich because of “privatization”.

As I was to continually find-out, “privatization” did make some people very rich but many others sold their vouchers for a pittance because their wages were not being paid while others simply handed over vouchers to managements when asked in the hope that wages might be paid in the future. In other cases, privatization was no more than straight-out theft! My suspicion is that Rodina never made anyone rich because its product could not compete with better imports.

There were a few companies in the Vladivostok area that were actually operating (for example, a soft-drink bottling plant and a large machinery shop which would have been focused of repairs) but many were dormant especially if in any way related to construction or metals on a large scale.

Vladivostok had several fishing fleets but also seemed to be mired in corruption with so-called “shareholder” meetings attended by large numbers of security people aligned with management or other interested parties. Fox eventually became a director of the large Far Eastern Shipping Company (FESCO) and, after reportedly upsetting the corrupt regional governor Yevgeny Nazdratenko and fearing imprisonment, fled Vladivostok for a time in 1999. But this was after I had finally left Vladivostok in 1996.

One theme that continually came up was the sudden halt to Soviet central planning of the economy by Gosplan. It caused chaos, particularly the sudden halt of entities access to financial resources.

It was after a return trip to Australia that I was asked by BBY shareholders in Pacific Gemini / Tiger Securities to take $US50,000 in cash with me I as went through Moscow on the way to Vladivostok. I was nervous about this being confiscated if I did not declare it at the airport and so it was decided that it should declare it. At the airport I was told to show it and count it out – while in sight of a bevy of taxi-drivers and assorted people in the arrivals hall about twenty meters away! To my relief I was able to catch a taxi and travel to the Intourist hotel without incident.

I was very reluctant to leave the $US50,000 in my hotel room and when I went to meet Evgenia – whom I had kept in contact with – I distributed the money in various pockets of my large coat. The weather was cold but the metro was warm so I unzipped the coat which meant that it tended to flap when I walked. I was suddenly surrounded by a large group of pre-teen age “gypsy” children who pawed all over me and took my wallet from my hip pocket. I grabbed a girl and repeatedly called out “thief” in my basic Russian. A policeman arrived and took me and the girl (whom I refused to let go of) to a police post inside the metro station. I called Evgenia and she eventually arrived just before one of the women associated with the children came to the police post and returned my wallet and its contents. I never let on to anyone other than Evgenia that I had $50,000 in my coat pockets!

It was during this time in Vladivostok that I met a Russian woman called Elena who was a law student and spoke excellent English. She was much younger than me and I fell in love.

It eventually became clear that Fox did not want me in Vladivostok because he and his wife were running the fund as a small private company with very little orthodox financial controls. Fox’s Russian was much better than mine and he seemed to want that I remain in the office to do desk research while he and his wife had almost exclusive contact with Russian companies in which shares could be bought. Fox was very intelligent but his mentality was more that of a dealmaker than an analyst. The best thing that happened was that Fox took me on a road trip that lasted several days (possibly because he was afraid to go alone) that visited a number of ports in the Primorsky Region of Russia, such as Nahodka.

When I eventually fell out with Fox and retuned to Australia, and Neilson had wised up to his antics, I asked Neilson to pay me a rather paltry sum to prepare individual company investment reports in the Russian Far East. He agreed and I eventually returned to Vladivostok to pursue my love affair. I travelled widely and prepared a dozen reports but there was little in the way of great investment opportunities. In Vladivostok I had been introduced to a physics student, Genardy, and with him I visited a number of organizations in places as Vanino and Khabarovsk. Little happened on the romantic front so I returned to Sydney. Neilsen said that my company reports were as good as he got from other people in other countries – even though I made no positive investment recommendations!

But, once again fate intervened to take me back to Russia! A group of Australian investors had become interested in reactivating an electronic blast-furnace in a closed-down large steel mill in the city of Komsomolsk-on-Amur. I was paired with a man who had been a metals analyst with a stock-broking company. He knew nothing about Russia and I knew nothing about electronic blast furnaces, so we were asked to do a joint report. We were taken to a large field with hundreds of mothballed Soviet tanks with the idea that they could be feed into the electric furnace but my supposed joint-report writer did not tell me that such armoured metal was unsuitable for this purpose; and he did not tell me the extent to which the blast furnace had been stripped of crucial electronic components; and finally when we sat together he would write with his left hand positioned so that I could not see anything – just like a young kid at school! We ended up doing separate reports. As it happened, a traditional blast furnace was operating on one part of the metal mill territory using parts of the tanks as input.

The only other notable thing about this visit was that we stayed in a single story solidly build and well-furnished building that had apparently been built for a one-night visit by Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev decades before.

On the way back to Australia I again visited Vladivostok and met Elena and invited her to Australia. To my surprise she was granted a visa and arrived in mid-1996. We got married and she became pregnant and eventually had a girl, and I found work as an economist – mainly on Australian taxation reform — in a business association. This was the start of a very difficult period in my life! After a divorce and many court issues, Elena managed to take our 7 year-old daughter, Anastasia, to Russia against my wishes. About a year later I managed spend a week in Russia and eventually found them living in St. Petersburg with Elena’s parents.

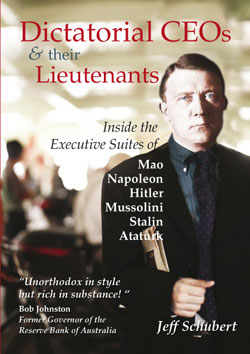

My daughter from my first marriage was now in her late teens and I was finishing writing my book, “Dictatorial CEOs and their Lieutenants: Inside the Executive Suites of Mao, Napoleon, Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, Ataturk.” After being confident that Anastasia’s grandparents would help me regularly see her I moved to Moscow with a visa provided by an organization teaching business English. After a couple of years I found that I could earn more money and choose my students by advertising my services in the media – both on-line and in the English language Moscow Times. I subsequently learnt a lot about Russian business conditions from students who were CEOs and senior executives in a large variety of organizations.

As well as teaching business English I began on online blog commenting of various government economic policies and articles in the Russian language media, which gave me additional issues to discuss with my students as well as improving my language skills.

I taught a wide variety of students, but two companies probably stand it. One was a sort of miniconglomerate that had several thousand employs in organizations such as dental clinics and maternity hospitals. The CEO told me that he would begin each day meeting his “head of security” rather than, for example, marketing or sales executives. He had initially accumulated capital by importing some earth-moving equipment from China using a large cargo aircraft and had sat in the driver’s seat of one of the machines all the way to unsure that it was not stolen!

Another miniconglomerate consisted of a jewellery store, a small factory making jewellery, a separate group of people sourcing and providing plants for offices, and a large structure which contained a down-market shopping centre and warehouse facility and a hotel of about 100 rooms. The CEO wished to sell the hotel but a big problem was that it had a common central heating system with the shopping centre and it would have been extremely expensive to separate the two. This situation apparently arose years earlier when local authorities wanted to promote tourism and only agreed to the centre-warehouse if a hotel was also built.

Occasionally the conversation turned to politics and mostly students expressed some concern about the future of democracy in Russia, but it was much more common for individual cases of corruption and bureaucratic obstruction to be identified. These ranged from problems with import customs, to needed individual cash payments to get things done, to difficulty in getting electricity connected.

One of my PwC students named Pavel progressed to being planning director for the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics and tried to employ me on his staff but was rebuffed by more senior executives.

One March day I received a phone call in response to my Moscow Times advertisements which mentioned my banking background. A man named Michael wanted to meet me and sent a white Humvee and driver to pick me up that evening. I tried to keep track of exactly of where we going but can only say with certainty that we ended up in the very upmarket Moscow suburban area of Rublyovka about 15 kilometres to the West of the Kremlin. The Humvee entered a walled compound with guards at the gate and a well-lit yard. When I climbed out of the Humvee I came almost face-to-face with a German-Shepard dog held on a lead by a uniformed guard, but neither made any attempt to stop me as I decided to walk towards the steps leading up to the huge white house.

I pressed the bell and the door which was opened by a slim black man of medium height with slightly greying hair aged about 50. My immediate reaction was that he was some sort of servant that an ultra-rich “new Russian” had employed to impress his contemporaries with his wealth and sophistication. The black man said hello, invited me in, and led me through a door into a study on the right side of the large hallway. It was only when the man went to sit behind a busy looking desk and started talking that I realized that this black man was Michael.

Michael now told me that he wanted to create a new bank in Moscow in partnership with Raiffeisen, an Austrian banking group which already had offices in Russia, and that he wanted my help in training staff. Michael said that “Geraschenko has already been here” to discuss the issue. I understood that Michael was talking about Victor Geraschenko, a Soviet-era banker who had later been head of the Russian Central Bank.

Michael said that he had come to Russia years ago to “sell cement”, had made a lot of money, and now wanted to help poor Russians by supplying cheap prefabricated housing because it was the “Christian thing to do”. I looked around the study as we spoke and apart from one desk, a cabinet, and a couple of chairs, there were only three large paintings on the walls. Each was of Jesus Christ with his disciples. They did not seem to be particularly good representations and, given the house that they were now hanging in, looked rather cheap.

Michael had not sounded particularly educated during the telephone conversations before the meeting, and this impression had not changed – although I found Michael to be quite charming in an unaffected way. Trying to get a better understanding of the situation, I asked Michael what he did before coming to Russia, and he said that he had been in the US Army as a “communications specialist”. Just then the door from the hallway to the study which was just behind where I was sitting opened. I turned to see an attractive dark haired white skinned women – most likely in her 30s – walk in and then seeing me quickly retreat and close the door. Michael continued the conversation as if nothing had happened.

Trying to understand Michael’s bank investment intentions, I asked: “Where do you keep your money now?” He replied: “In houses.” I interpreted this answer as buying real-estate, but as the conversation continued, I realized that Michael was saying that he kept large amounts of cash in houses. If true, I thought, this would account for the guards I encountered when I arrived. Michael said that he needed his “own bank”.

I digested this strange situation for a moment and was about to ask Michael why he needed his own bank when a black women came into the study through a door near Michael’s desk with a small tray of food. Michael said that he worked “24-7” (24 hours a day, 7 days a week) and that “they are always trying to fatten me”.

Michael did not touch the food and pushed the tray away after the women left. This was not easy because the desk was crowded with several laptops and piles of papers. Michael picked up a closed laptop and repositioned it on the desk, saying: “I have got a new computer and don’t know what to do with this old one”. I had recently purchased a new computer and faced the same issue, which gave me a slight feeling of empathy with Michael. In fact, I quite liked him. He communicated in a matter-of-fact way with a relatively flat voice. Further conversation in which Michael talked about his “big US corporation” did not help my understanding of the situation.

Michael then said that his driver would take me back to my apartment. Michael led me out of the study into a directly connected kitchen and then through another room back into the hallway and the front door. It was about 8 in the evening and sitting around the kitchen table were a number of black-skinned female adults watching equally black-skinned children frolicking in a large indoor swimming pool situated on the other side of a full-sized glass wall.

Michael offered no explanation for this scene. Of course, there was no reason why Michael was obliged to do so but the strange combination of the very expensive house and cheap paintings, unexpected variety of people – including the patrolling guards – and Michael’s unusual financial claims had me totally intrigued. And then there was the white woman who had briefly entered Michael’s study!

Michael had previously given me his business card. It said: “Michael Patton, Group Executive Director, Sovereign Group, Sovereign (AGES) Bancorporation, American Modular HITEC, US Global Projects Ltd, American Billex Credits Ltd, 140 Blundell Road, Luton, Beds, LU3 1 SP, UK Tel: +7499 347 7695, +7926 515 7865

Email: sovereigngroup@live.com and. sovereignagesbancorporation@live.com

When I tried to find more information on the internet, it turned out that the only information was some registered address in the UK of the type that was probably little more than a post-office box. There was nothing to suggest that Michael was head of a “big” US corporation.

I later found that Sovereign (AGES) Bancorporation had only been incorporated in the United Kingdom on 5 March — only weeks before, with Michael one of two directors under the name of “Michristly Gmichael-McPatton”, with a birth date of April 1964. His nationality was described as “American”, while country of residence was Russia, and address for correspondence was “H.2, Bld. 1/6, Arhangelskiy Lane Moscow, Ru, 101000. “Michristly”! This was strange, but the “christ” part fitted in with Michael’s words about being a Christian and paintings on the wall in his study. The other director listed was a Victoria Derbina, described as a Russian national born in June 1979 whose occupation was “investor”. Victoria’s address for correspondence was listed as Bolshoi Predtechensky St. 23-48, Moscow, Ru, 123022

Neither of these physical addresses gave any indication of being possibly associated with Michael. The other company names on Michael’s business-card gave much the same information about both Michael and Victoria. In addition, there were a number of Russian, British and American nationals listed as directors at various times, but I could find no additional information about them.

I was now impatient for Michael’s next call which only came about a week later. This time a late model white luxury Mercedes Benz took me to the same address as before and – like the Humvee – was immediately waved through the guarded gate. I thought it odd that Michael used a different telephone number every time he called. I later started writing the number of each new call on the back of Michael’s business card but gave up after writing down three: +7 909 959 5323; +7 964 708 4418; +7 965 145 1173

At this second meeting I decided to ask him about this and other questions arising from my internet searches, but Michael’s unusual request made me completely forget. Michael wanted me to “urgently” fly to New York and withdrawer “a heavy amount” of money from a US bank, buy a large house “just like the one we are in now” and live there with large amounts of cash in the cellar. I would have taken up the offer out of curiosity but said that as an Australian I needed a visa to enter the US, to which Michael simply and calmly replied: “I forgot about that.”

My strange conversations with Michael and my internet research had convinced me that Michael was a con-artist and not to be believed. But, I wondered, how did this explain the extremely expensive house and the guards? And how to explain the black women in the kitchen and children swimming in the pool at 8 in the evening – presumably they lived there!

On 28 March I sent a short email to Michael on sovereigngroup@live.com – saying “just making contact” – to which Michael gave a short “OK” reply. I next heard from Michael in mid-April – again from a different telephone number — and Michael wanted to meet me near my apartment. I waited near Kuklachyov’s Cat Theatre on Kutuzovsky Avenue.

Michael arrived in a tan Mercedes station wagon that was probably around ten years old with a Russian woman – who was a decade or so older than the one I had seen enter Michael’s study during our first meeting. Michael explained that this tan Mercedes was his “personal car” as he did not want to draw attention to himself with a flashy car like the ones that had taken me to our meetings. The women got back into the car and left with the driver. Michael later told me that he had become “quite close” to this woman, leaving me with the impression that other relationships had become frayed.

In his typical low-key way Michael requested that we not stand on the sidewalk of busy Kutuzovsky Avenue but instead go behind some buildings because he did not want to be in a “public place”. I momentarily had a vision of being shot at and readily agreed. Michael said that he had hired Victoria as an interior decorator and eventually made her his business partner, but she had betrayed him in cahoots with some other Russians. Michael said he had some “temporary” financial problems and wondered whether I knew of a bank that could lend him money until he could “sort things out”. I tried to explain that – in my new life in Russia – he did not know any bankers, and that even if I did there was no apparent reason for them to lend Michael money.

About nine months earlier at the end of summer I had been sitting and drinking beer in an outdoor café not far from the covered Bagration pedestrian bridge across the Moscow River, which connects Kutuzovsky Avenue to the main Moscow international business center with its numerous high-rise buildings.

I eventually struck up a conversation with the only other customer – a blackman! He said his name was Jim and that he had come to Moscow from Chad decades ago to study at the People’s Friendship University where he was now a professor of chemistry. He had married a Russian woman and lived nearby. Just as we had finished exchanging contact details a Russian woman appeared walking towards the café and screaming at Jim, causing him to hurriedly say goodbye to me. A few weeks later when Jim’s wife was visiting relatives, we had another beer and I was shown Jim’s nice apartment in a building on Kutuzovsky Avenue. I got the impression that Jim’s wife was bit of a tyrant, but the two remained quite devoted to each other as he explained that he was “waiting” for her to “return” from her relatives.

After the last meeting with Michael behind a building so as not to be seen in a public place, I called Jim and explained the situation with Michael and that I really wanted to “solve the Michael mystery”. I suggested that Jim be introduced to Michael as a wealthy potential investor. Given that Michael had called me from various telephone numbers, I dialled the number from the most recent call.

Michael readily agreed and surprisingly arrived on foot at the agreed meeting place, a small park area not far from Jim’s apartment, a few days later. The meeting lasted about an hour and took a strange turn with Michael continually talking about the “need for air-conditioning” in Africa. As air-conditioning was nothing to do with any of my previous conversations with Michael, I took this to be a pitch to Jim for money on an issue that might interest him. Jim said that he would call a childhood friend who was now a senior official in Chad to discuss the issue. The meeting then ended up without a conclusion, with Michael saying he would later contact Jim.

“He is from Nigeria!”, Jim exclaimed as soon as Michael was out of earshot. I was less sure. I had met several Nigerians during my years in Russia, mainly younger people who were working in informal jobs after overstaying student visas. Their English had some unusual characteristics which Michael did not have; although I am the first to admit that I have little talent for languages. After Michael later called, Jim told him about my reason for organizing the meeting. Michael called me one more time after this and wanted to borrow a very small amount of money to stay the night in a hotel – but I declined. Michael then told me that I was “dishonest” for claiming that Jim was a rich potential business partner.

In those days – before the Russian invasion of Ukraine – McDonalds fast-food chain had a very large store situated across a narrow street from a pleasant Novopushkiinsky Park, which itself is separated from Pushkin Square by the very busy Tverskaya Street. The large statute of Pushkin on Pushkin Square is a popular meeting place with good access to three connected metro stations. If Michael wanted to hide somewhere, this was not the place!

But, on a warm June day I walked through the park toward McDonalds and saw Michael sitting alone on a bench. I went up to speak to him and found him polite but non-talkative. Michael’s bag was half open next to him and I could see several mobile telephones. Several days later I again saw Michael in the park – wearing exactly the same light-coloured clothes as previously, suggesting that he did not have any other. I never saw or heard from him again.

During the period of our meetings I told many people besides Jim about Michael, the house and guards and people in it, and his unusual claims and requests. All were astonished but none had any explanation!

In the same year as the Michael Patton saga I had my my first serious interaction with Russian police and — as I will relate later — had even more interaction with them in Irkutsk some years later. In both cases I found the criminal police to be very professional.

One evening I was as browsing on a dating site when I came across a photo of a dark-haired woman proudly displaying extraordinarily long fingernails. She as very attractive with her profile saying she was 34. I sent her a message and eventually we agreed to meet in Tsaritsyno Park, which is a very large and attractive place in the south of Moscow with many fountains and Tsarist-era buildings.

The woman, who was taller than average and of slim build, arrived with her very active son – aged about 8 – and an attractive blond female who was supposedly going to meet her boyfriend in the park. The blond actually seemed to have a nicer personality than the woman with long fingernails, and I was initially happy that her boyfriend never showed up.

I spent a couple of hours walking with them before we all went to a cafe inside the park. While they ordered food and drinks, the boy began making a clear nuisance of himself by running between tables and trying to take things off them. I went to the toilet which was situated in another small building close by and when I returned to the café there was a huge fight underway with – to my amazement — both women physically swinging chairs at other diners.

I left the café when the two women did but got no answer when I asked what had happened. It was dark and pouring with rain and we managed to hail a taxi which took us to a nearby apartment. All of us were totally soaked and I stayed in the main living room while the others went into another room. I took off my wet jacket and shirt and put my wet passport and wallet on a table to dry. The boy suddenly came out of the other room and began randomly picking-up my things. When I tried to stop him, he began screaming. The boy’s mother came out of the other room and immediately attacked me, trying to gouge my eyes with her long fingernails. Her female friend made some effort to stop the attack and said “sorry” to me several times!

I grabbed my wallet and banged on the door of another apartment yelling for help because the women had followed me and was still trying to gouge my eyes. I punched her hard in the face and she retreated to her apartment. The police eventually arrived and took both myself and the woman to a police station. As I explained what happened – including showing photos of woman on the dating site – I heard much noise and banging upstairs. “Is it her?” I asked. One of the police nodded. Unfortunately, I had not managed to grab my passport when I fled the apartment because the boy had thrown it somewhere – and the women denied having it. I was then taken to a doctor who applied some medication to the scratches on my face.

The next day I returned to the police station but was told the women continued to deny she had my passport and there was nothing the police could do about the situation. After a couple of days when the scratches were less obvious, I went back to the café in Tsaritsyno Park to ask what happened. I was told by a waitress that the boy had been running around the café pulling things off tables and had been asked by one of the male customers to stop. When the boy persisted, the customer grabbed his hand. The boy had screamed and this led the woman with long fingernails to attack him with a chair. The waitress described the women with the long-finger nails as an “animal” who had also attacked a security guard and ripped his shirt with her fingernails.

I later received a message from the woman claiming that I had molested her son and demanding money as compensation. This would have worried me if he had not been back to the café to find out what had happened, so now I just ignored the demand. But there was still the problem of the passport! I offered to pay some money to get it back but got no reply.

My apartment on Studencheskaya Street, not far from Kievskaya metro station was on the ground floor. A number of tall trees in a small plot separated my living room window from a walkway. For over a year I observed that between 4pm and 5pm a well-dressed man aged about 50 would walk three small dogs. One day I was in a small grocery shop nearby and the man came in and we struck-up a conversation. His name was Peter Lavelle, host of a Russia Today (RT) television show called “Cross Talk”. For a while we became quite friendly. He had done a PhD in European history and had come to Russia in the late 1990s after spending a number of years in Poland where, amongst other things, he said he moved money for the Kaczynski twin brothers who were involved in political activities. In Moscow he had initially worked for a stock-broking firm before turning to journalism.

There was a self-appointed moralistic streak to Lavell who expressed disgust of what he saw (and maybe even participated in) when he first came to Moscow. For some reason he had been drugged and was found lying under a car with no shoes in winter and said that he nearly lost his feet as a result. Lavelle was a strong supporter of Putin whom he described as a “great man”. We met a few times and I joined an email chat group that he ran. He took great exception to me disagreeing with him on a relatively minor issue and thereafter refused to talk to me. I have occasionally come across people who know him and there is a general view that he is intolerant of other views – something that is evident in his “Cross Talk” show. Lavelle has now reportedly become a Russian citizen.

In Moscow I had my first stay in a Russian hospital with some sort of food poisoning – and it was thanks to Kostya that I was well looked after.

I was a fairly active traveller visiting such Russian cities as Smolensk and Rostov-on-Don. I also travelled to Uzbekistan (Tashkent and Samarkand), Azerbaijan (Baku), to Yerevan in Armenia by taxi from Tbilisi in Georgia, and to Kiev (where I experienced numerous low-level attempts to trick money from me).

In the meantime, Vladimir Putin had returned to the presidency and I became pessimistic about further reform efforts. My ex-wife Elena had taken Anastasia from Russia and had cut contact with Anastasia’s grandparents as well as me. I was then to lose contact with my daughter for ten years! Thwarted on a number of fronts, I decided to try living in China because of its better business opportunities and greater relevance to Australia.

After considerable effort to learn Mandarin from Chinese living in Moscow I arrived in Shanghai. When I moved to Russia I could practice my Russian reading in a variety of ways from street signs to printed newspapers. This was impossible with Mandarin and I made no progress in any real sense on anything until I was told about a research contract that some Australians had with the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics but were unable to complete for some reason. I managed to insert myself into this and spent some months doing research – both reading and survey – of Shanghai’s future prospects of becoming a top-level international financial center (IFC). Some of my work resulting from this can be read at: https://www.shanghai-ifc.org

At a regular “social gathering” of mainly non-Chinese people hosted by a Chinese man from Taiwan who had business interests in Shanghai, I was told that the Shanghai branch of AustCham (Australian Chamber of Commerce) was in dispute with the Beijing branch and wanted to do its own “white” (discussion) paper on Chinese financial sector reform. Consulting with AustCham members, I eventually did this and it was launched by then Australian Treasurer Scott Morrisson at a lunch in February 2016. This report can be read in pdf form at: https://shanghai-ifc.org/jeff-schubert-in-shanghai/

As I needed to periodically leave China for visa purposes I visited Moscow in mid-2015 and sent out an email to the large number of people whom had earlier emailed my economic commentary to. I got a reply from Vladimir Mau, Rector of the Russian Academy for National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA) who it turned out had been a fan of my commentary. We met and I gave him copy of my book on “Dictatorial CEOs”. This led to a job offer and in 2016 I returned to Moscow to become, at my suggestion, inaugural Director of an International Institute for Eurasian Research.

My first RANEPA activities were actually in China in March 2016. My new Institute deputy director had previously worked in RANEPA’s international relations department and he met me in China where he organized that I give a lecture at Beijing International Studies University as part of an effort to attract Chinese students to RANEPA. I chose to talk about the South China Sea, Crimea and One Belt One Road (which eventually became the Belt and Road Initiative or BRI). I repeated this lecture at Shandong University but it was too controversial and there was no third lecture. The photo on my LinkedIn profile was taken in Beijing and the whole lecture is available here: https://www.slideshare.net/citizenmurdoch/south-china-sea-crimea-similarities

My new Institute’s reality turned out to be less grand than its name implied, and while I was warmly welcomed by people who reported to Mau it became apparent that some noses were out-of-joint because funding for this Institute had come from other areas where it may have been more readily available for misappropriation.

My official need for a medical examination was avoided by submitting the records of someone else!

In Moscow I rarely encountered obvious display of opposition to the government except for the several times that I saw protestors pulled from the stand supporting the large stature of Pushkin in central Moscow. The was always a bus parked nearby which contained a number of policemen. They would tolerate a lone protestor carrying a placard but would quicky move in if others sought to join the protest.

Over the years I was in Moscow during several annual military parades, but the most impressive thing was the 9 May “Immortal Regiment” when hundreds of thousands of people parade through central Moscow carrying photos of relatives who served in some way in 1941-5 “Great Patriotic War”.

Not long after I arrived at RANEPA, my friend Pavel (from PwC and then Sochi Olympics) become a senior executive in the National Technology Initiative (RTI) organization and invited me to give a presentation on a flotilla of boats — Foresight Fleet — sailing down the Volga River from Moscow. The RTI was concerned with local technology development in the resource rich Russian economy – an issue of relevance also to Australia – and I put considerable effort into preparing my presentation.

The cruise itself was not particularly interesting but I did get into a disagreement during a group discussion with a particularly opinionated Russian man who was a strong technology nationalist. About a day later we had a glass of wine together – to the surprise of some other people, including a Russian woman who now lived in America. The man’s name was Andrey Bezrukov who had lived in the USA under the name of Donald Heathfield for many years as a Russian sleeper agent. Bezukov did not strike me as a particularly unusual either in intelligence or personality. He was just an ordinary man – and perhaps this was one of the reasons that Russia had selected him to be a “sleeper-agent” spy!

After the completion of the “Foresight Fleet” river cruise I wrote a report that was very critical of the “foresight” approach to issues and what I regarded as excessive focus on developing local technologies rather than importing them. To my surprise my immediate boss at RANEPA (who had a Ph.D in art history and reported to Mau) was dismissive of it because it was not “academic” enough. My report, which I subtitled “Waiting for the High-Tech Tooth Fairy”, can be read here: https://russianeconomicreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/NTI-English-Version-end-footnotes-RJE-revised.docx-for-pdf-1.pdf

I convinced him that my next effort would be better. I travelled to Kazakhstan and eventually wrote a long report looking at Russia’s international relations in the context of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In the meantime, RANEPA sensitivities had been increased with the November 2016 arrest of Economic Development Minister Alexei Ulyukaev. who was a friend of Mau and co-author of several articles with him. My report was criticised on a number of fronts by my immediate boss – including the use of the term “annexation” to describe the 2014 Russian takeover of Crimea. Given the sensitivities, I decided to not take up the issue with Mau.

The 2017 summer holiday period was approaching and I was concerned that the large amounts of data in my report would become dated if publication was delayed till after August. Unable to get RANEPA to commit to publication under its name I published, with the subtitle, “Noodles and Meatballs in a Breaking Bowl” on my own internet site. See: https://russianeconomicreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/New-Eurasian-Age-with-Chinese-Silk-Road-and-EAEU-in-SCO-Space-1.pdf )

I emailed it out to my list and received a very positive reaction, including from the Asian studies section of the prestigious Higher School of Economics (HSE). I then spent two years part-time teaching Masters degree students a course on Russian foreign policy in Asia. All but a handful of my 30 or so students were Russian and most of them were interested in China, although about 5 wanted to specialize on Korea (both North and South). Nearly all spoke very good English and were generally impressive students.

After the first year was completed I noticed that the Indian Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA) was organizing a conference on international relations, so I registered, got an Indian visa and purchased a flight to New Delhi. However, a sudden deterioration in India-Pakistan relations led to the conference being cancelled. I complained to IDSA and was invited to spend some days at the campus as their guest. As well as many discussions with IDSA analysts I spend some time next door with Shashi Asthana of the United Services Institution of India. I also travelled to Punjab University and gave two lectures, including in its Defence Studies Department, and lectured at the University of Rajasthan in Jaipur. I also met members of the New Delhi Policy Group. The main topic of these lectures and discussions was Russia-India relations and when I got back to Moscow I added India to the group of countries covered in my HSE lectures.

In Moscow (and later when I lived in Irkutsk) I always made an effort to attend annual Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC) two-day conferences on Russia-China Relation. A pattern emerged that on the first day senior officials from both countries said very nice things about each other. However, by the second day criticisms emerged – and these were sometimes very strong. I have written several articles that have been published on the RIAC internet site. See: https://russiancouncil.ru/en/jeff-schubert/

I also found Valdai Discussion Club seminars in Moscow quite useful.

Not long after this an Australian delegation of self-proclaimed “greybeards” – to mean experienced and sagacious former officials – led by Paul Dibb, and including Nick Bisley, arrived at the premises of the RIAC. Attending the meeting at the invitation of the RIAC, I could not get a handle on what they hoped to achieve.

My former deputy at RANEPA, Dimitry, returned from a period teaching in China to establish a BRICS Institute at the Irkutsk National Research Technical University in 2017. This seemed an odd place to establish such an institute but the BRICS pay was better than HSE and I had a close relationship with Dmitry. He booked me on a flight to Siberia to check things out. It was late spring and the weather was great and the facilities were impressive.

My first class as a professor of international business included 14 Chinese students who spoke poor English (and no Russian) plus 3 Russian students. My second class consisted of over 60 Chinese students with generally poor English. In both cases I found that the best approach was to start with examples of balance sheets and income statements because they at least understood numbers. When I got onto more wordy conceptual issues I found some of them continually trying to cheat.

I had another class which had a higher proportion of Russians with good English and – trying to be inclusive – hit upon the idea of using articles from the Wall Street Journal. Not only were the articles quite diverse, including on Chinese issues, but they could be listened to. I hoped to get through to students with poor English by a combination of reading, listening and then speaking. Post COVID19 some students had been stranded in China after returning for the Chinese New Year and we communicated on Voov which would, frustratingly, be disconnected on occasion. I eventually realised that these disconnects would only occur when we attempted to listen to articles discussing certain sensitive Chinese issues!

Irkutsk (population about 650,000) turned out to be a very nice city. It is big enough to have large shopping centres where it is possible to buy almost anything that you would expect in a much larger city but small enough to be able to walk to most needed places in the centre. It is situated on a river and is not too far from Lake Baikal. Irkutsk winter is cold with an average January winter day of about minus 20 Celsius – the coldest day that I experienced was minus 43 — but nearly always sunny, while summer August days averaged around plus 20.

I can say that I enjoyed working in Irkutsk more than any other place – and I have worked in many even before I became chief economist of an Australian bank 10 years before I first went to Russia. This enjoyment was partially due to the subject matter that I was teaching and partly due to the challenge of dealing with Chinese students, but mainly due to the highly intelligent university staff that I worked with. They were mainly Russian, but I also become very good friends with a chemistry professor from India and with several IT and maths professors from Iran.

My blog about Russian economic and business issues had also attracted international attention, and in June 2019 I was invited to Bavaria in Germany by the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies to talk about the Russian economy. Various people who attended his talk in Germany were intrigued that I was living in the “middle of Siberia”. “Why would you want to live there?”, they asked.

There was also a flow of visits to Irkutsk by Chinese academics and officials and some interesting discussions. One Chinese official who was introduced to me as a “leader” of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), laughingly said that Chinese understood the concept of “Greater Eurasia” because they read the writings of Russian polemicist Sergei Karaganov. He also thanked Donald Trump for pushing Russia and China closer together.

It was in Irkutsk that I had my second stay in a Russian hospital after over-indulging in strong painkillers because of my – life recurring – back problems which sometimes have almost totally incapacitated me. The hospital was basic but comfortable and I was treated well.

Later I was to cause some controversy by my refusal to wear a mask during COVID19 and where possible to avoid restrictions on movements which were often illogically imposed by zealous individuals with influence over some activity rather than by officials. For example, an outdoor exercise area on university grounds was roped off by attendants in a nearby dormitory. Several people around me did become ill but – despite being the oldest person – I never felt ill. I may have been able to be so uncooperative because the university rector had been required to take a COVID19 test before meeting a visiting Moscow official and recording positive while feeling totally fine while he continued his daily exercise routine. I eventually had to accept vaccination so that I could fly to Moscow.

Before COVID19 I had flown from Irkutsk to Moscow a number of times. On one of these flights there seemed to be an unusual number of men in uniforms. I had a pleasant conversation with the man not in uniform in the seat next to me. It was only when I was collecting my baggage from the carousal and I saw him handcuffed to one of the men in uniform that I realised who I had been talking to. If I had known I would have asked him about his crimes!

It was also in Irkutsk that I had my second significant dealings with Russian police and got an insight into the court system.

Once again on a dating site in Irkutsk, I contacted an attractive Russian woman. Veronica seemed very young and her messages suggested that she was very intelligent and spoke reasonable English. She said that she had a job as a waitress in a café in what was considered a down-trodden area in the northern part of Irkutsk, but it was not enough money to leave home and get away from her parents who were “always drunk”.

On a very cold spring day Veronica arrived at our first meeting at a “Papa Johns” pizza restaurant near my apartment. She was wearing an old jacket that did not look very warm. In a moment of compassion – and, in truth, trying to curry favour – I offered to give her money for a new jacket and use my phone to make a transfer to her Sberbank account from mine if she would let me see her passport because her family, Akhmetzhanova, seemed too complicated. She did not have the passport with her but sent me a photo on WhatsApp which suggested she was 21 years old.

Veronica never arrived at a planned second meeting, saying that she had been in a taxi which had crashed because the driver was drunk. Just fifteen minutes prior to our next meeting about a week later, Veronica texted that she had to cancel because her two “cousins” would arrive from another city. I invited them all to my apartment.

Wary of being drugged – as had happened in Moscow in the mid-1990s – I drank only beer from a narrow top bottle held in my hand while the women drank red wine from glasses. I thought that Veronica’s “cousins” seemed almost too nice – with much almost crocodile-type smiling but little conversation – and began to wish I had not invited them.

Veronica and one of her “cousins” went together to my apartment’s bathroom. I thought little of it until they did it a second time and I realized that my mobile phone – which was unlocked because I taken some photos – was no longer on the table. When they came out of the locked bathroom, I grabbed my phone and could see that some kind of transaction had occurred with my Sberbank account. All three women then fled the apartment.

Running to another apartment, I begged the occupants to call the police. Two uniformed officers eventually arrived, with one holding a Kalashnikov. While I explained to the two officers what had happened – a significant amount of money had been transferred from my Sberbank account – a third plain-clothes officer arrived unannounced and began rummaged through my laptop. I was then glad that there were no incriminating photos of any sort on it.

Soon a two-person forensic team arrived. Photos of both the apartment and myself were taken and I was both finger-printed and prints taken of both hand palms. I eventually got to bed about four hours later, and the next morning went to a follow-up interview at a regional police station. There were a number of officers who came and went from the meeting at various times. Some of the police seemed a little sceptical of my story and I recounted what had happened to several different officers over the next couple of hours. It was around mid-day when one young detective sitting in front of a computer began smiling.

Thanks to a very efficient police communication network – and probably lack of separate legal jurisdictions – Veronica had been arrested in a Moscow airport that morning after a 6-hour flight from Irkutsk. It turned out she was only 17 years old. Veronica had “photoshopped” the passport photo which she had earlier sent to me to show that she was 21. The passport number had not been changed, only her birth date!

Veronica then spent a couple of days in custody in Moscow sending me numerous WhatsApp messages offering some sort of compromise deal in which she paid the money over a period of time. Even though she quickly sent some of the money, she did not send even half of it so I rejected a deal. Veronica was eventually returned to Irkutsk under police guard and was held in jail for several days while police investigated further.

Veronica was brought back to my apartment to re-enact part of the events while photos were taken. I was surprised how cooperative she was but she also seemed a little shocked about the situation that she was now in. After much work and several more meetings with me, the police put together an impressive looking case brief around 2 centimeters thick. I was asked to review it to check for mistakes. It was not the first time that he had been impressed by Russian police involved in low-level criminal matters.

A date was set for Veronica to appear in court several weeks later after she was released on bail. As during the joint interview in my apartment, a public official was present in court to advise Veronica because she was aged less than 18. During the court hearing it emerged that Veronica had seen and memorized my Sberbank access code in the App on my phone during the first time that we had met. What she then needed was access to my mobile phone when it was unlocked so that she could open the Sberbank App and make a transfer from my account to hers.

Strangely, I admired Veronica’s audacity in transferring money from my Sberbank account to hers, even though such stupidity resulted in a “paper trail”. At one stage Veronica told the police that the money had been transferred in return for sex in – of all places – the bathroom while the “cousins” waited in the main living room. There was a single bed set against a wall in this large living room which was occasionally used by one of my friends and Veronica and her “cousins” probably assumed that this was my bed. In fact there was also another room with a large double bed where I slept. The very young Veronica and her “cousins” probably hoped to disappear into the vast Moscow urban space with little understanding of its monetary costs and consequences.

The court date finally arrived and I was present with an Russian interpreter from the university. The court room was a rather small room on an upper floor of a non-descript building although set out in much the same way as a typical Australian court. It was revealed that Veronica had a very extensive criminal history, with shoplifting and other stealing offences beginning at a very young age. In this case a very tearful Veronica admitted her guilt to the court, and her nose started bleeding – possibly from stress! Veronica’s mother – who had clearly been drinking – was present in the court and the female judge directed a lot of adverse commentary at her for being a poor example to her daughter.

Veronica promised to repay the money and a separate future court hearing was planned that would consider Veronica’s intent and ability to repay the money. So far, I was very pleased about how things were proceeding! But it turned out that I would need to prepare an official claim with legal assistance for this future hearing, which I eventually decided not to do given the cost and great doubts about whether any judgement in my favor could be enforced. Veronica might go to prison if she could not pay, but apart from revenge this was of little use to me.

The February 2022 invasion of Ukraine had no meaningful impact on my life – although it was a factor in my decision to finally leave Russia in October 2022. For some time I had ambitions to make short films and most of my days were spent learning to use Apple’s Final Cut Pro software. I had a greenscreen in my apartment and was making some – what I thought – very innovative clips with comparatively cheap Russian actors. Alas, AI can now better produce the sort of things that I attempted. At this time I had another – and the worst ever – back injury that was so severe that I was initially advised that I would need laser surgery. I was basically incapacitated for several weeks.

I had several friends who strongly supported the Ukraine invasion. In a couple cases it was because they had relatives in the mainly Russian speaking provinces of Ukraine but post-2014 images of killed people in these provinces also built support. And there was basic Russian nationalism. While many young men fled Russia to avoid being drafted into the army, I knew several who did not purely because they did not have sufficient money.

The biggest surprise for me was how quickly and completely people – even close friends – adopted the term “special military operation” (SMO or SVO) even when I referred to “invasion”. There was an echo here of my experience at RANEPA years before when I had written about the “annexation” of Crimea. While there was some official efforts to increase support for the SMO there was no mass outpouring of support.

My short-film activities were interrupted by an email inviting me to New Delhi to speak at a Indian Department of External Affairs in-house conference on Russia-China relations in the era of Putin and Xi. I prepared a long report as background to my presentation, which can be read here: https://russianeconomicreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Russia-and-China-in-Eurasia-1.pdf )

After that, I did not return to Russia – bringing to an end around 12 years of involvement over a 31-year period!

I then wrote and published a modified version of my book on Dictators which includes Putin, called “PUTIN and his Lieutenants: compared to Mao, Napoleon, Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, Ataturk”. A Kindle version can be purchased from Amazon at: https://www.amazon.com.au/gp/product/B0DBGYB3RR